Improve

Improve Your Breathing

Developing a good breathing technique is essential to good singing, but understanding the mechanism of breathing in general and gaining control of a proper breath management does need time and a lot of practice. Before we lose ourselves in the depths of our anatomy and read through a myriad of well-meant literature and helpful instructions however, the probably most important and helpful consideration should be kept in mind first:

Breathing is a natural process of our body, and we should never force it or make something unnatural out of it. Good technique comes natural and unforced.

- Why do we want to work on our breathing?

- The act of breathing

- The different ways of breathing

- Why is our breathing routine not optimal for singing?

- How can we train breathing?

- Appoggio

- Avoid these common breathing mistakes

- Exercises

^ Why do we want to work on our breathing?

A proper breathing technique is required for the singer to be able to sound great and improve on the voice's overall tone. Managing breath can have positive and also negative impact on the quality of your voice. It is therefore desirable to gain control over your breath and with it the tone of your voice, which results in improved abilities as a singer and which builds a base for an overall healthy environment.

Controlling your breath enables you

- to control your voices' tone by adding or avoiding airiness

- to increase your ability to sustain notes

- to sing longer phrases more effortless

- to increase the volume of your singing voice naturally

- to improve the condition of voice and body

- to lesson the tension in chest, shoulders, and neck

- to lesson the pressure on your vocal folds

^ The act of breathing

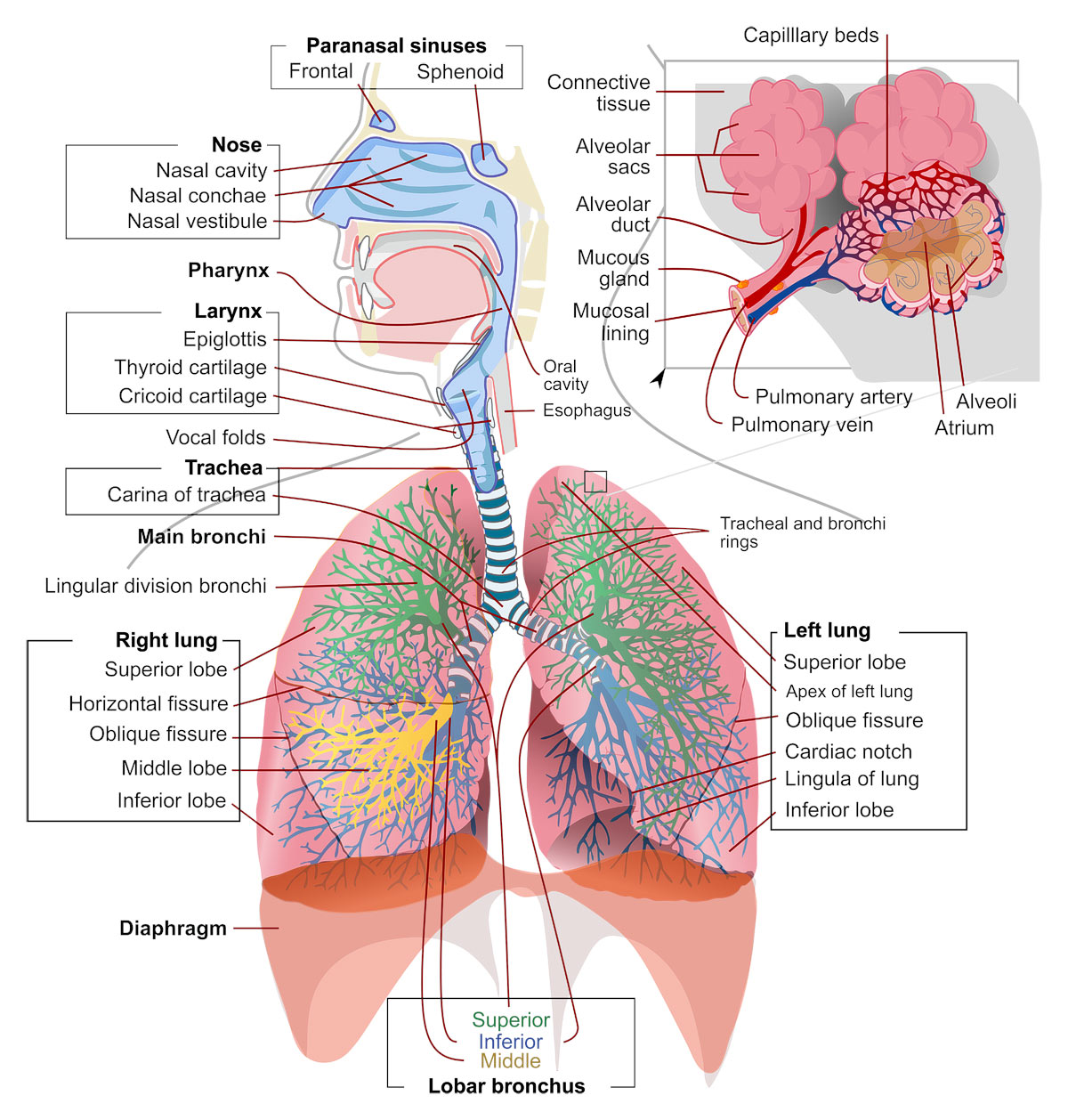

Almost effortless and without our adding we breathe around 12 to 20 times each minute of our lives. We do this to transport life-sustaining oxygen into our body, and to dispose carbon dioxide out of it. During the breathing process we contract and expand our lungs with help of the diaphragm, a dome-shaped muscle system that is inserted into the lower ribs right under the lungs.

The diaphragm tightens or contracts downward when breathing in, which creates a vacuum that causes fresh air to flow into and fill the lungs. When we inhale air through nose and mouth the air will travel down the back of our throats into the windpipe (trachea), which divides the air guiding it into the two bronchial tubes. Those tubes are leading to smaller air passages (bronchioles) and end in tiny air sacs (alveoli), which are surrounded by a mesh of tiny blood vessels (capillares). It is here where the oxygen passes through the walls right into the blood.

Once the diaphragm relaxes, it will cause the lungs to deflate by pushing upwards onto the lungs, which triggers the exhalation process. Exhaled air travels from the lungs through the windpipes to either nose or mouth. If the air passes the laryngeal level and meets resistance through a set of closed vocal folds, the vocal folds begin to vibrate and the sound of our voice is produced. A singer wants to learn slowing down the relaxation of the diaphragm to gain extra volume used for sustaining notes and sing longer phrases.

Thankfully the breathing process has a direct link to our conscious mind, which gives us control to start or stop our breathing at will, and to choose the amount and pace of air we inhale or exhale in a given breath. Any sound we produce is fuelled by breath, so the ability to control the flow of air is essential for the various demands and dynamics of singing.

The respiratory system consists of the airways, the lungs, and the respiratory muscles that mediate the movement of air into and out of the body.

^ The different ways of breathing

Our body offers a number of different ways for the breathing process to choose from, which depends on situation and choice. However, for the singer one particular method is to prefer.

Costal breathing

During costal breathing (also called chest breathing) the inspiration and expiration of air is produced by an expansion of the rib cage. Though costal breathing can be used for singing, it is mostly not the first choice, simply because the limited diaphragmatic descent does not allow a complete breath and reduces the ability to control breath pressure and flow during exhalation.

Clavicular breathing

During clavicular breathing the upper chest and lungs expand during inhalation, triggered by muscles of chest, shoulders, upper back, and neck. This results in an elevation of the upper rib cage and chest during each inhalation. For the purpose of singing this type of breathing is not beneficial, because the collapse of the rib cage forces the air to expel rapidly and with little control, producing either a breathy, tight or pinched sound. Beside the limitation of not being able to take a full breath, the movement of the rib cage will cost more strength.

Abdominal breathing

During abdominal breathing, also referred to as belly breathing, the air intake results in a protruded lower stomach. This allows the diaphragm to descend fully allowing a deeper breath. Abdominal breathing is an acceptable choice for singing, especially if a singer lacks depth and a sense of ground during breathing. On the downside the lack of rip cage movement may result in bad body alignment and slouching.

Diaphragmatic breathing

The diaphragmatic breathing combines the costal breathing method with the abdominal breathing method resulting in a full descent of the diaphragm with simultaneous elevation of the rib cage. During inhalation the abdominal muscles relax and the external intercostals expand the rib cage. During exhalation the abdominal muscles gently engage while the external intercostals keep the rib cage expanded. By allowing the abdominal muscles to control the exhaling process the singer gains full control of how to use the breath.

^ Why is our breathing routine not optimal for singing?

Though the breathing mechanism for all the different daily activities including speaking and singing is always the same, the regulation of airflow differs depending on our bodies' demand for air. When we speak or rest per example, we tend to inhale and exhale more even and shallow simply because our body doesn't require as much oxygen. If we on the other hand exercise on a physical level, our body demands more oxygen and we need to breathe deeply to fill this demand.

Depending on our personal development and lifestyle we may pick up a routine that may be interfering with the demands the task of singing generates. As more time we spend walking on this planet we tend to develop a laziness resulting in shallow breathing. Other factors like bad habits (e.g. smoking), health issues (e.g. obesity), or simply caused through aging weigh in as well.

Age related changes to our breathing may be measurable in decreasing peaks of airflow, a weakening of the respiratory muscles, and a decline of the potency of lung defence mechanisms. Though this doesn't necessarily translate into recognizable symptoms, it may have an effect of a person's ability to do vigorous exercise. Thankfully there's a lot we can do to counteract such issues and by improving our health in that matter we might gain the means for a better breathing among other benefits.

When we sing we require a higher rate of breath energy and an elongated breath cycle in comparison to speaking. Especially when we sing intensely, our body compensates the demand for oxygen by inhaling more quickly and deeply, and by exhaling more slowly and steadily.

^ How can we train breathing?

To train breathing means to train the control and coordination of the muscles supporting the work of the diaphragm and the function of the larynx. Contracting the abdominal muscles during the diaphragm's relaxation process gives performers a means of controlling their sound and phonation. In literature this is referred to as "support" or "breath support". The idea is to extend the capability of breath management and to elongate the breathing cycle, while gaining a better tone production and the ability to sing extended phrases and to sustain notes for longer.

Breath management is defined by the ability to control the amount and pace of air that flows through the vocal folds, and by the ability to keep the stream of air as steady as possible to create a steady singing tone. It includes the ability to reduce the stream of air to a bare minimum in order to gain more efficiency.

Achieving breath support is done through influence of the abdominal muscles, and can be reached by either using additional muscle force during the act of exhalation when sound is produced, or by relieving the muscle force during the act of inhalation to lesson air pressure allowing more time during exhalation.

This sounds terrible complex at first, but lets take this apart a bit further:

When we utilize our muscles of the abdominal wall to create a force that counteracts with the process of the relaxation of the diaphragm, we create an increased air pressure in the lungs that either lead to an airy and breathy tone or is responsible for the glottis pressing the vocal folds more firmly together resulting in a delayed start of the sound. With this technique you will achieve a louder voice, but you will not be able to hold that additional volume for very long.

If you choose to relieve the tension of the abdominal muscles during inhalation, you will end up with less air pressure in the lungs to begin with, which in turn makes it possible to slow down the exhalation process to the extend that you can sing longer. The technique also supports long-term vocal health and will result in a more rich and steady sound, because the air pressure pushing towards the vocal folds is more appropriate.

^ Appoggio

The latter method is also known as Appoggio and popular with the international classical singing community as an integral component of the "Italian School" of singing, which includes resonance factors in form of phonation alongside breath management. Appoggio strongly depends on body posture and the interplay of the different muscles used for singing.

Appoggio can be understood as an extension of the natural breathing process, that enables the vocalist to pace his or her breath more efficiently through gaining control over the breathing mechanism by training the involved muscles. The basic concept is to gain a balance between the muscles of inhalation and exhalation in such a way, that it enables the vocalist to control the amount and speed of air that reaches the vocal folds. The vocalist controls the airflow with help of the abdominal wall muscles, which are connected to the diaphragm.

To achieve Appoggio breathing, the singer will have to keep head, neck, and rib cage in a proper alignment that allows the ribs to expand and the diaphragm to descend properly. The elevated rib cage will become a foundation for stabilizing the muscles connecting chest and larynx, and will be maintained throughout the breathing cycle.

Once the vocalist inhales, the lower rib cage will expand to the front, the sides, and slightly to the back. The diaphragm will descent and the main muscles of the lower abdominal wall will expand laterally, the stomach does not push out or pull in at all.

At the start of exhalation the larynx and throat should remain open and free with no sense of grabbing. The vocalist will attempt to remain in this position as long as possible, meaning he or she will hold the torso and ribs in the position throughout the exhaling process. Chest and sternum (breastbone, a narrow bone that is connected with the clavicles and ribs) will remain elevated without much of a falling or rising movement. The vocalist will try to maintain the lateral expansion as long as its comfortable, but ultimately the expansion will fall towards the end of the exhaling process.

Appoggio breathing gives the vocalist a number of valuable benefits:

- Maximum control over the airflow

- Longer air supply through use of less air

- Better stability in the singing tone

- Improved speed, accuracy and clarity in singing

- Raised confidence in your vocal skills

^ Avoid these common breathing mistakes

Here is quick checklist of common breathing mistakes the vocalist should avoid. This is a general guide, of course a specific singing style might let you break the rules.

Don't take in too much air!

The more air is inhaled, the more air pressure is build up below the larynx. Ideally the vocalist only breaths in as much air as is needed for the task. Make it your mission to know how much air you need.

Don't force the air out!

Let the air flow out naturally while you sing, otherwise you might end up with a pressed phonation (sounding forced) or with a breathy voice. If you force air out you will lose breath quickly and your tone of the voice will become unsteady as a result.

Don't hold the air back!

If you do, you will produce unwanted subglottic pressure which strains your voice and could lead to potential injury. Holding back the air will make you sound less steady and free.

^ Exercises

Understanding the theory behind how the body masters the task of breathing builds the base for the vocalist to improve upon his or her own breathing technique, however the singer also needs to build an understanding on an experimental level. For this reason we have collected a few exercises here.

^ Hissing Exercise

This exercise aims for a smooth and even sound, demanding an economical use of the available breath. It is simply done by breathing in to a specific count, and then breathing out to another count while creating a hissing sound during exhalation.

Go through the following counts

- in for 4, out for 8

- in for 2, out for 8

- in for 6, out for 12

- in for 4, out for 12

- in for 2, out for 12

- in for 6, out for 16

- in for 4, out for 16

- in for 2, out for 16

- in for 6, out for 20

- in for 4, out for 20

- in for 2, out for 20

- in for 1, out for 20

^ Sustaining Vowels

This exercise aims to avoid subglottic air pressure by training the coordination between the breathing mechanism and the larynx. It is done by sustaining a vowel in a comfortable pitch (taken from the speaking range). Start off with a clean tone, then seamlessly switch over to a breathy tone, and finally end the vowel with just a stream of air. Keep the pitch during the whole exercise. Go through the vowels and then start again with a higher pitch and repeat.

Go through the following vowels

- "Ah"

- "Eh"

- "Ee"

- "Oh"

- "Oo"

^ Snatched Breaths

This exercise aims to give the vocalist more control over the amount of air intake. Instead of breathing in all the air for a full lung capacity, the air intake is interrupted into a changing number of steps. Make sure to keep a position in favour of the Appoggio breathing method, and to avoid any tension in the throat during the process. Breath out gradually by the number of steps outlined in the exercise.

Go through the following counts

- in for 4 x 1/4 capacity, out for 8

- in for 3 x ~1/3 capacity, out for 8

- in for 2 x 1/2 capacity, out for 8

- in for 4 x 1/4 capacity, out for 4

- in for 3 x ~1/3 capacity, out for 4

- in for 2 x 1/2 capacity, out for 4

- in for 4 x 1/4 capacity, out for 2

- in for 3 x ~1/3 capacity, out for 2

- in for 2 x 1/2 capacity, out for 2

^ Farinelli Exercise

The Farinelli Exercise will help the vocalist to develop the supporting inspiratory muscles that help maintaining a lowered diaphragm. It is a good exercise to prepare for the Appoggio breathing method, because it helps the vocalist to pace his or her breath flow and to keep the diaphragm in a lower position for longer.

The exercise has three equally long phases

- Inspiration

- Suspension

- Expiration

During inspiration the singer inhales air evenly over a count of 3 seconds to the full capacity of the lungs. Make sure not to overcrowd the lungs with air, and keep your overall body posture in favour of the Appoggio breathing method.

During suspension the breath cycle is paused for 3 seconds, keeping mouth, nose and the glottis in a natural open position. This means that no pressure builds up, and that air could hypothetically flow in and out of the open breathing tube. In fact no air flow will happen with a resting diaphragm; if it does it would mean that the singer has taken in too much air.

During expiration the singer will exhale the air over 3 seconds in a steady and even pace. There should be no urge to gasp at the end of the cycle.

After completing all the phases of the exercise, the vocalist can then repeat the steps with an additional second added to each of the phases. The singer can do this multiple times, always adding another second, until the maximum length of his or her ability is reached. At the beginning and by average the singer will end up with a cycle of 18-21 seconds. Once the maximum is reached the singer can then count backwards, going through the exercise by taking off a second for each of the phases until the initial count is reached.